It was Darrel Bristow-Bovey’s bucket-list wish to see the gorillas of Virunga. We sent him, and there he discovered a surprising, beautiful kind of heartache. Photos by Teagan Cunniffe.

Gorillas are herbivores and spend their days digging up roots and stripping away branches and leaves to reach the fibrous hearts of palms and ferns.

Also read: Behind the scenes – photographing gorillas

A friend once told me that after seeing the gorillas she started having terrible nightmares in which she was a little girl taken from her family. In her dreams she walked barefoot and alone at night, crying for her mother, looking for her in the dark shadows under hedges. She would wake with her cheeks wet with tears and an unfixable feeling of loss.

I’m suspicious of people who claim spiritual connections with animals. I once went swimming with wild dolphins in Mozambique. Everyone in the group had expectations, but when we dropped off the boat and the pod moved past us, fast and grey like muscular shadows, it was clear we meant nothing to them – we were a lumpy gaggle of something unappealing, a raft of seaweed with legs. Back on shore I listened as the others rhapsodised the moment of contact:

‘Did you see that? He looked at me!’

‘Me too!’

‘It’s like they wanted to communicate!’

Human beings have strange expectations of the smart mammals they go to meet in their natural environment, and sometimes those expectations overwhelm common sense. In the early morning at the trekking centre in Kiningi in the Northern Province of Rwanda, I sipped bad coffee and listened to the nervous chatter of the others around me.

‘My heart won’t stop racing,’ said one American, and I saw her fingers tremble as she fastened her protective gaiters. ‘I feel like I’ve been waiting for this all my life, without even knowing it!’

‘I think I’m going to throw up,’ agreed her friend.

A middle-aged English woman named Sally stood staring up at the mountaintops. Earlier she’d told me that she has only one lung. She looked nervous: even with a full complement of lungs, she’s probably larger than optimal trekking size.

The Volcanoes National Park spreads over 8000 square kilometres of the Virunga mountain range, joining with the national parks of the DRC and Uganda to create a united Mountains of the Moon, encompassing nine volcanoes, three of them active. On trek day you’re assigned to a small group of six or seven with a guide, and set off in search of a specific family. Bands of gorillas roam on random orbits, making a temporary nest overnight then moving on at first light, and they range high and low and far across the volcanoes. Your band might be 10 minutes away or at the end of a half-day’s climb through jungle and dripping cloud forest.

Sally was already breathing hard just with the exertion of tilting back her head. Did she really want to do this? ‘I’ll see them even if it kills me,’ she wheezed.

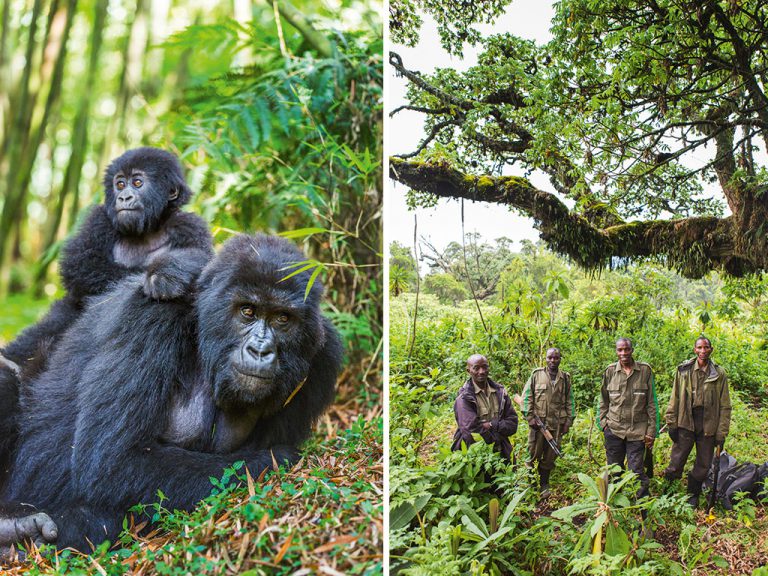

LEFT: a baby gorilla peers quizzically from among a bamboo thicket. Contact between gorillas and trekkers is forbidden, as the apes can catch colds or flu from humans and possibly die. RIGHT: the Kwita Izina naming ceremony, where children dress like baby gorillas, is evidence of how the local community has a sense of ownership of the gorillas.

The gorillas are a big deal to everyone. From the moment you land in Kigali you notice three things: the streets are clean and safe, the country is plastic-free, and gorillas are everywhere. They’re on billboards and taxis, on banknotes and T-shirts. Rwanda is a tiny country with a dark recent history and small mineral resources, but over the past five years the economy has grown at least six per cent annually, and the gorillas are the single biggest foreign currency earners.

A decade or so ago Rwanda solved its poaching problem – hungry villagers were setting traps for buck and buffalo and gorillas were collateral damage – by letting the community share the benefits. The villages surrounding the parks provide guides and trackers; poachers are rehabilitated into blue-uniformed porters who carry camera bags and backpacks for a $10 fee. Tourist funds are channelled back into local infrastructure; we drove past a local hospital being built entirely with park fees.

At Kwita Izina, the annual ceremony at which invited dignitaries formally name the baby gorillas born during the year, the surrounding communities are invited to a free music concert before the ceremony. Children dress in baby gorilla suits and the crowd cheers each of them and each new name. Anyone you speak to knows the names of the gorilla family groups and has something to tell you about them – there’s a sense of ownership which may explain why gorilla numbers increase each year on the Rwandan side, while on the Congolese and Ugandan slopes they are under pressure.

When Dian Fossey made her observation camp between Mount Karisimbi and Mount Bisoke in 1967, she predicted the mountain gorillas wouldn’t survive until the end of the century in the wild. In 1981 there were only 242 individuals left. Today the estimations are around 800, as high as 1000. There’s something almost disconcerting about a conservation story with a good tale to tell.

LEFT: babies draw their confidence from contact with their mothers and then venture out bravely to investigate the strange new arrivals. None of them is anxious or afraid. RIGHT: the trackers are drawn from the villages and communities on the fringes of the national park. They spend 12 hours at a time following family groups and predicting their movements.

We drove up a rutted track through ploughed chocolate-brown fields worked by women with scarlet headscarves against a backdrop of hazy blue mountains. We took walking sticks and water bottles and climbed a low stone wall and found the walking track that Dian Fossey created, snaking up through bamboo thickets and dense forest hung with lianas and tree ferns.

We were six: One-Lung Sally, clutching her porter’s hand like a teenager on a date; Gaius from Uganda on his 13th trek; Jens from Switzerland with a camera that cost more than my house; Teagan the Getaway photographer who shrugged 25 kilograms of equipment on her back and went bounding up the mountainside like a young gazelle; Emmanuel the guide, who as a boy used to chase away the gorillas from his family’s potato fields and help his brothers set snares that would sometimes sever a gorilla’s paw. Without the gorillas, he told me, he’d still be out in the fields but instead, a few years ago, he was named Rwandan Guide of the Year. As part of his prize he went to Kigali – the first time he’d ever left his village – then flew to Dubai – the first time he’d ever left Rwanda – then flew to Tokyo. His eyes grew wide.

‘Tokyo is not like Rwanda,’ he said.

The air was moist but cool with altitude and the light was green in the forest. The canopy rang with the songs of birds whose names I’d like to know. We found an earthworm half a metre long. Somewhere around us were forest elephants and buffalo, and somewhere above us were gorillas.

We hauled ourselves for hours vertically through mud, and we all stopped to lean on our sticks and gasp and suck at the thin air, except Teagan, who offered to carry my pack for me and randomly picked up rocks and tree trunks and carried them a little way uphill on her shoulder, just for the fun of it.

Sally was pale and doubled over, still holding her porter’s hand. One of the trackers pointed above us and we scanned the green face of the volcano. I saw some leaves shake, then I saw a bird suddenly rise, then I saw nothing. The trackers shook their heads and frowned. There was a faraway rumble and the light changed: a storm was coming.

It doesn’t matter if we don’t find them, I told myself. It’s the quest that matters: to be out here walking the Mountains of the Moon, halfway between the crater lake and Dian Fossey’s gravesite. You don’t have to see the gorillas to feel them: it’s enough just to be here, just to look for them.

And then Emmanuel started making a low series of keening grunts and moans. For a moment I thought something was wrong, but then I followed his eyes.

We climbed the hillside, off the track now, pushing aside fronds and bamboo stands. There’s a species of stinging nettle that looks like normal nettle, and when you’ve left the path and you aren’t wearing long trousers or gaiters because you’re South African and therefore tough, it burns your calves like a spray of sulphuric acid.

When you slip on a steep-sided slope and grab a stinging nettle to stop yourself sliding it’s as though you’re being seized by a robot jellyfish, but you don’t cry out because right there in front of you, too real to be real, is a family of gorillas.

A veteran male silverback sits watch over his territory and family. A few weeks earlier he had killed another silverback in a battle for dominance.

The male silverback is sitting a little way up, a hairy Mussolini scanning the hillside for rivals, surveying the distant town of Musanze like a citadel he might later choose to sack. He glances at you then looks away in contempt. You aren’t a rival; you’re smooth and weak and unworthy. Across the hillside, small mounds of coarse blackness in the green, is his family: the twitchy blackback young males, the pot-bellied wives, the small bundles of wrestling babies.

There are noises – grunts and pants and yodels and sighs – but they’re all from the guides and trackers, performing the vocalisations that Dian Fossey identified on this very slope half a century ago. There’s the cracking of roots and twigs, the crunching of fibrous bulbs. A young male uproots a plant and solemnly strips it while staring at the black clouds on the southern horizon.

After all the walking and the anticipation it’s dizzy, surreal: they’re right here. We tiptoe breathless over collapsing bridges made from branches pulled down by gorillas. We sit almost among them, and then they stretch and wander and move around so that we are among them, and they’re among us.

A baby climbs onto his mother and goes tumbling as she rolls over onto her side. He staggers to his feet and sees me and starts tottering curiously towards me. I hold my breath – I want him to touch me, I want to be chosen to receive his contact – but Emmanuel hisses and gestures, and I have to stand and back away, not because his parents would mind the contact, but because of our germs. Gorillas can catch flu from us, and the common cold. We can kill them with our breath. Even in the moments of our greatest vulnerability, the threat is always from us to them.

For a weird moment I think this can’t be real. These are men in gorilla suits: their hands are too shiny and plump – they look like bad imitations, like extras dressed as outer-space apes in an old episode of Star Trek. But they must be real, because a human actor couldn’t imitate those feet. Why did we leave those feet behind on our genetic journey? They’re an extra pair of hands, complete with thumb. If we had feet like that we could write a letter and drive a car and eat sushi, all at the same time.

I don’t believe in spiritual connections between animals and humans, but that’s not to diminish animals. They don’t need connection – they’re the happy ones, we’re the meaning-making animals trying to impose our stories onto them. But I understand now why my friend had her nightmares of being alone, after seeing the gorillas.

In the hour you spend with them, you become overwhelmed with the affection. Constantly, non-stop, they touch each other. Kids climb on moms, siblings tussle with siblings, grown males reach out and touch their brothers just to let them know they’re still there. Only the silverback stays aloof, but even he comes over and brushes against one of his children, or offers himself to be groomed. I wouldn’t call it love – we’re the only primates to evolve fancy-pants ideas like that – but in all the touching and reassurance and comfort, you can see where love evolved.

Being there among them, you can’t help thinking about the world we’ve made, the stresses and splintering, the fears of our own devising. You can’t help thinking about every child separated from its parents in Syria and Serbia and Rwanda and back home. It did something to my heart to watch them – the security they must feel, the freedom within safety. It made my heart ache a little. It made me want to call my mother.

LEFT: A tracker leads the way up the path Dian Fossey made on Mount Karisimbi towards her research camp. After her death, her body was carried back up the mountain to be laid to rest beside Digit, her first and favourite gorilla friend. RIGHT: a baby gorilla lies fast asleep in its mother’s lap.

Getting to Rwanda

I flew Kenya Airways from Johannesburg to Kigali via Nairobi. Prices are from R6000 return. Be prepared for the fact that flights leave after midnight, arrive in Nairobi around 5am and land in Kigali mid-morning. Carry a change of clothes and toiletries in your carry-on luggage: turnaround times are short, and Nairobi is the Bermuda Triangle of luggage. Three times, on three different routes, my suitcase stayed behind in Kenya. It has always eventually found me, but interim clothing makes the lag more bearable.

The best time to go to Rwanda

Rwanda is a little south of the equator, so it doesn’t have a distinct summer or winter season which means gorilla tracking is possible year-round, but impossible when it’s raining. Gorillas are like us: when there’s water falling, they prefer to stay undercover. It’s best to avoid the rainy seasons: March to May and October into November. June to mid-September is the best time to visit.

Need to know

South Africans are required to purchase a 30-day visa on arrival. It costs R400. The currency is the Rwandan franc (RF) but US dollars are widely accepted. Riding pillion on a moto (small motorcycle) is the best way to get around. It’s also exhilarating and quite fun. From R15 per person for a 15-minute journey.

What to do in Rwanda

Go gorilla trekking in Volcanoes National Park (obviously). Depending on where the gorillas are, a trek can be anywhere from two to four hours, including spending time with the gorillas (around one hour). It costs R10075 per person for a permit which includes a guide and park fees. There are only a certain number of permits allowed per day and these must be booked well in advance.

Tel +250252576514.

Visit the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre. The events of 1994 are carefully reconstructed, placed in historical and colonial context and graphically relayed. There are written texts, photographs, video material and a truly heartbreaking children’s section at the very end that brings home the full horror. Make time to stroll the grounds, and visit the burial site of some 250000 of the approximately 800000 to one million victims. Open from 8am to 4pm daily. Entrance is free.

Tel +250788303098.

Stroll through Kimironko Market – it’s clean, reasonably priced and teems with goods and produce. You can buy everything from veggies to kitchen appliances, but the real gem is the fabrics. Browse colourful designs, make a selection – about R90 for 2 x 3 metres – and head over to the women standing by with their sewing machines. You can choose what style of dress or shirt you want made and then pick up your new outfit within a few hours.

Where to stay in Rwanda

Lemigo Hotel is popular with tourists, businessmen and conference attendees. It’s 10 minutes from both the airport and the city centre. The staff is friendly, the rooms are air-conditioned and there’s a poolside restaurant with an unnervingly large menu. Evening entertainment includes bands and local music video screenings. From R3000 per person, including breakfast.

Tel +250784040924.

Iris Guest House has basic accommodation (facilities could do with an upgrade) but it’s clean, central and a good budget option. From R700 per person sharing.

Tel +250788465282.

Where to eat and drink in Rwanda

Rwanda has a variety of local brews. Mutzig, although owned by Heineken and first brewed in Alsace, France, is regarded as a premium local beer. It’s full-bodied, delicious and cheaper than imported beers but slightly more expensive than my other local favourite, Primus, which has 0.3 per cent more alcohol than Mutzig but feels lighter and more refreshing.

Shokola Storytellers’ Cafe is an Afro-European style spot on top of Kigali’s public library. The menu is mostly European and prices are aimed at tourists, but it’s a great place to grab a smoothie (from R70 each) and watch the sun set over the city.

Tel +250788350530.

Sol e Luna is a popular Italian restaurant. It’s set in a double-storey terraced house, with multiple wooden platforms covered with fairy lights and creeping plants. Pizzas are from R82 each, there are 100 different kinds.

Tel +250788859593.

This story first appeared in the December 2015 issue of Getaway magazine.

Get this issue →

All prices and contact details correct at publication, but are subject to change at each establishment’s discretion.

You may also like

Related Posts

Our columnist, Darrel Bristow-Bovey, transforms into a dashing Frenchman of the World....

read more

It takes time to find your happy pace, reflects Sally Andrews....

read more

'No one can say I’m not romantic,' proclaims Darrel Bristow-Bovey, reflecting on a Valentine's Day...

read more